Jane’s Addiction’s Ritual de lo Habitual

With Jane’s Addiction’s Ritual de lo Habitual heading for its 30th Birthday, Getintothis’ Mark Walton looks back at the troubled path of a classic rock album.

Jane’s Addiction‘s Ritual de lo Habitual is transgressive and transformative, confounding and confrontational.

It is the very epitome of sex and drugs and rock and roll.

It starts with a stop and climaxes in the middle with a singer who casts himself in the role of Christ. It shattered the band that made it but broke the dam for others to pour through.

And it takes in racial tolerance, philosophy, environmental concerns, art, feminism, suicide, one of rock’s most famous menage a trois – oh, and nicking stuff.

Born out of its own members’ chaos, Ritual de lo Habitual landed 30 years ago in a music world in flux. Hard rock was water trying to find its level. That level, when it was eventually reached, turned out to be grunge.

But before that came two years of wild creativity, of some of the most interesting music of the Eighties as that decade turned into the Nineties, in many cases far more appealing than what would follow in the wake of Nirvana and Nevermind.

Back in 1990 ,hair metal still strutted its coiffured stuff. Yes, thrash led by Metallica had changed the scene forever but it pulled up the drawbridge to most other influences and, let’s face it, those bands – with the sub-genres of black/death/doom on the horizon – didn’t always give the impression of having tons of fun.

For listeners looking for something else, something a bit different, Faith No More, Living Colour, Soundgarden, early Red Hot Chili Peppers, and the first Smashing Pumpkins album offered exotic, livelier alternatives.

Even more traditional metal outfits like Queensryche and Kings X produced their finest work in this period while up in Quebec Voivod put out their sci-fi tech-metal masterwork Nothingface in 1989 and New York’s Warrior Soul never bettered their 1990 debut Last Decade Dead Century.

Los Angeles’ Jane’s Addiction were far from new, having already released the equally groundbreaking Nothing’s Shocking in 1988, a studio follow-up to their live debut album (there’s a whole other article to written on whether Shocking or Ritual is the better record). So expectations were high for its successor.

The circumstances of its recording, though, could hardly have been less conducive to great work.

Singer Perry Farrell and guitarist Dave Navarro were strung out on heroin at the same time as bassist Eric A(very) was trying to get clean while drummer Stephen Perkins, who eschewed hard drugs, was left to hold it all together. “They were just more into getting high than working,” he said.

And yet somehow these disparate characters gelled as they often do in dysfunctional rock bands, at least for a time.

Nirvana’s Bleach turns 30: A relentless two-chord garage beat laying Cobain’s sonic foundations

Reflecting on Ritual’s 25th anniversary for Rolling Stone, Navarro, who barely remembered the recording sessions, said: “One of the things I really loved about those days … was that all four of us had extremely different sensibilities, and we kind of all fought for our space and our voice. In my opinion, all four of those spaces and voices were aligned on that record, more so than anywhere else.”

Since Farrell and Avery weren’t speaking, they refused to be in the studio at the same time, as confirmed by producer Dave Jerden in Brendan Mullen‘s oral history of the band, Whores: “[They] decided they would come in a different times to do their stuff“.

There was, however, one crucial exception to this working-together-separately approach, as we shall see.

Not that their ambitions were in any way diminished. Navarro says that “The Velvet Underground, Led Zeppelin, Bauhaus, Van Halen and Rush were all part of our sound” so they were getting in the ring with the very best.

And Farrell‘s ego, never a small thing, dominates proceedings. Lyrically, thematically, from the title to its infamous cover image, Ritual is his baby.

Crucially, as he revealed to Rolling Stone many years later, he’d saved the best songs the band had written for their second album (in which case they had some truly great second-rate tunes, given the magnificence of Nothing’s Shocking) because he wanted to guard against accusations that it was “a sophomore slump“.

“We were at the peak of our powers as a band, so I felt that this was our time to really come out and blast people with sonic sounds that they would groove to for the rest of their lives” he said.

In so many respects he got his wish.

Released in August 1990, Ritual de lo Habitual – the ritual of the habitual, named after a gig residency – still exerts a mighty pull on alternative music. It sounds nothing like Nevermind but it was a pathfinder that lit the signal fires to the mainstream which Cobain and co only had to follow.

But let’s not begin at the start with that stop, but instead in the middle where the album’s centrepiece, the mad, majestic Three Days.

Eleven minutes long, it deliberately and self-consciously sets out to join the canon of rock epics. Stairway to Heaven, Free Bird and Dream On were cited by the band as their benchmarks, while it also bears comparison with another alt-epic of a later generation in Paranoid Android.

It’s an account of the three days that Farrell and his then girlfriend Casey Niccoli spent in drug- and sex-fuelled bliss with a young artist called Xiola Blue who died of an overdose in 1987, though the song was apparently written before her death.

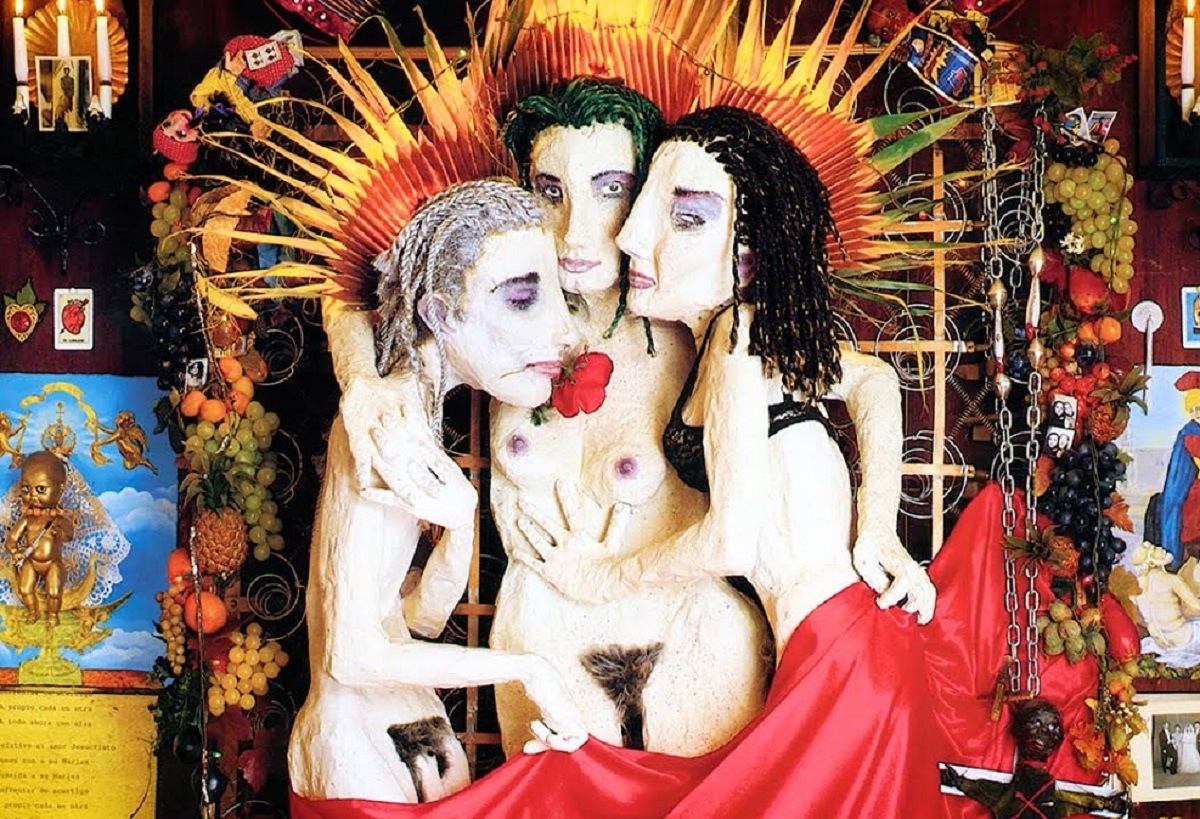

It also inspired the infamous cover with the three lovers reproduced as papier-mache sculptures in bed, influenced by Santeria, the African religious tradition that developed in Cuba, and Christian imagery.

The sight of Farrell‘s meat and two veg peeking over the blanket meant that for surely the only time in music history, a band managed to fall foul of the censors with a sculpture cover for the second time running, each time featuring the same woman (Niccoli).

Farrell’s response was to release some copies blank apart from the First Amendment, instantly creating collectors’ items as everyone bought the uncensored version.

“At this time you should be with us...” Three Days opens with a spoken word intro which continues almost inaudibly as the music starts gently, driven as so often by Avery‘s bass, such a feature of JA‘s sound, until the singer’s shout of “Go!” lets the band off their collective leash, Navarro‘s extended solo gradually giving way to a chugging rhythm section with serrated guitar lines, building and building, before Farrell’s climatic cry of “Erotic Jesus…lays with his Marys/Love his Marys” and the throbbing tribal drumming takes over.

It can be no coincidence that this was the one occasion that Dave Jerden was able to get all four in the studio and record Three Days in one take. Said Navarro: “It really tells a great story. It doesn’t give a fuck about structure; it doesn’t give a fuck about verses and choruses, but every part is memorable — you get lost in it.”

If that wasn’t enough, there’s a footnote that only emphasises the song’s grandeur and folly: it was released as a single, which on the 7in version meant splitting it in two. The two parts are included on the Live and Rare compilation from 1991, clocking in at 8 minutes 14 seconds for the first and 2:34 for the second. Simply gloriously mad.

Steve Lamacq interview – from Nirvana to Aphex Twin, a life in music

From Ritual’s peak we drop back down to the start and Stop!. A woman’s voice intones in Spanish: “Ladies and gentlemen, we have more influence over your children than you do. But we love them. Born and raised in Los Angeles, Jane’s Addiction!”

As opening statements of intent go it’s hard to better – even in a language foreign to American and British listeners.

Navarro‘s slashing chords herald Farrell shouting “Here we go!” and we’re off, dragged into the breakneck, helter skelter world of Ritual de lo Habitual.

This is a record of two very distinct sides and on the first it often sounds like the musicians are playing in different bands – no surprise given the recording process – and yet it coalesces into some meaningful whole greater than the sum of its parts.

Stop!‘s pell-mell pace switches to a sudden time change and a satisfyingly muscular power trio section – that Rush influence revealing itself? – before Farrell sings a capella and Navarro strums along, Avery and Perkins no doubt being physically restrained from joining in until the optimum moment.

Throughout Ritual Farrell’s words are elusive and allusive, ostensibly stream of consciousness but thought out and deeply personal. They are also often barely decipherable, even with a lyric sheet, but here he seems to be pleading for everyone to give the world a break from environmental damage and the sheer speed of human existence – “lit to pop and nobody is gonna stop” … “turn off that smokestack and that goddamn radio“.

There’s barely a breath before we’re into No One’s Leaving. In this clarion call for racial inclusion, Farrell drew on his sister’s experience of being kicked out by her family because she had a black partner: “My sister and her boyfriend slept in the park/She had to leave home ’cause he was dark/Now they parade around in New York with a baby boy… he’s gorgeous“.

Yet again Avery‘s punk-funk propels proceedings while Navarro fires off salvos of strafing guitar. At their core, Jane’s Addiction adhere to the template laid down by Van Halen: a shit-hot guitarist backed by an airlock-tight rhythm section and singer who’s gonna do his own thing no matter what.

The Van Halen comparison wasn’t always a positive one. Dave Barbe of Sugar was not convinced by their credentials: “People can’t be looking at things like Jane’s Addiction as some sort of alternative. It’s just corporate dick rock. It’s Van Halen with different make-up artists.”

Jane’s Addiction were signed to Warner Brothers, so were in no position to claim Fugazi-level independence or integrity, but their musical promiscuousness far outstripped that of Dave Lee Roth and his cohorts as they absorbed reggae, funk, dub, and folk alongside their staple hard rock sound.

And how many “corporate dick rock” bands would have got away with the impromptu interlude of Ian Dury‘s Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll that follows? It’s hard to think of an outfit it more squarely applied to.

Farrell’s ad-libbed “Take that fucking piss-cup outta my face” probably alludes to his deeply resented spells in rehab at the time.

Musically, there’s no let-up as another monstrous bass riff kicks off Ain’t No Right, as clear and concise a summary of Farrell‘s worldview as Jane‘s oeuvre contains: “Ain’t no wrong now, ain’t no right/only pleasure and pain“.

It sounds purely amoral, a utilitarian, even animalistic approach to life. But dig a little deeper and the singer argues it’s a positive thing. He enjoyed getting into dangerous situations because he knew how pleasurable it felt to get out of them. And here he predicts the Youtube generation of extreme thrillseekers.

All this is put to bubbling, hyper-kinetic (hypersonic, to reference a much later Jane‘s song) rhythms and unstoppable guitar with divebombing plane effects thrown in.

Phew, time to take a moment.

Obvious settles into a more downbeat, reggae vibe, a warm musical bath with piano played by Farrell in the background and Navarro‘s guitars slathered on top, as the singer rails against some individual intent on doing him down on his way to the top – “I worked my fingers to the bone and I won’t let you stop me going up” It was, said Navarro, “the closest we sounded to being from outer space“.

Very much down to earth is Been Caught Stealing, rock’s greatest hymn to half-inching. It’s the ironic side effect of success that Ritual‘s best known number is also its most throwaway. Hear a DJ announce a Jane’s Addiction song and you can be sure it’ll be this one.

What Dave Jerden said they all considered just to be “a fun track” – complete with barking accompaniment by Farrell‘s dog – was sent on its way to ubiquity thanks to its video.

Directed by Casey Niccoli, it features a chap in drag purloining stuff from a supermarket while a pole dancer does her thing and the band, as was their wont, get their shirts off (Kerrang! noted that “Farrell and Navarro in particular seemed to go for decades at a time between shirts“).

Whether by design or default, with Stealing Jane’s managed to tap into a musical zeitgeist thousands of miles away.

He wouldn’t have been wearing flares when he laid them down but Stephen Perkins‘ drum patterns were deemed close enough those of the Stone Roses and Happy Mondays for Simon Reynolds in his Melody Maker review to proclaim: “Its funk undercarriage is almost baggy!”

Three Days, as we’ve seen, most certainly wasn’t baggy and the band followed one side two epic with another, though Then She Did… manages a mere eight minutes.

Bikini Kill asked for revolution in the 90s, why are they still waiting?

After all the rocking-out the tone here is pastoral, Zepellin III to Three Days‘ Zepellin IV, but that only belies the darkness of the subject matter, the most troubling on the record as Farrell imagines the unfortunate Xiola Blue meeting his mother, who took her own life when he was an infant, in some afterlife – “She was unhappy just like you were“. The song’s quieter passages almost fade out altogether only to then presage the coming storm: “Now the nameless dwell“.

More bad things dwell in Of Course, centred around Charlie Bisharat‘s folk violin reflecting the band’s interest in Zydeco music and The Velvet Underground.

It’s a skewed, upside-down nursery rhyme, a place of peril and darkness: “Of course this land is dangerous!/All of the animals/Are capably murderous.” The world is Where The Wild Things Are.

So it’s a relief to end matters on a genuinely, untainted positive note, with Classic Girl, which could be a companion piece to Summertime Rolls from Nothing’s Shocking.

Farrell set out to write about love from a romantic angle rather than the machismo prevalent among most metal bands. He said: “I was hoping that people would fall in love to this song, or get married and walk down the aisle to Classic Girl. The name of the game of life is love.”

It can’t be said that its musicians always loved each other, but such has been the appeal of Ritual de lo Habitual that it remains cherished and revered 30 years on.

Somehow an album that could only have been made in the sunshine and madness of California transcended those origins and resonated with so many – as a twentysomething in the Midlands my life at the time was light years away from the members of Jane’s Addiction but no record meant more to me in 1990.

There was a heavy cost to pay for it though. The band essentially agreed to tour and split up.

Farrell and Avery weren’t talking while Navarro, according to his cousin Johnny, was maintaining a $700 a day heroin habit.

Relations hit an all-time low on the first night of their Lollapalooza musical revue tour when guitarist and singer came to blows on stage.

It couldn’t last and it didn’t: in Hawaii in September 1991 Jane’s Addiction played their last show. Farrell and Perkins performed naked.

In the ensuing three decades there have been numerous compilations, offshoot groups (Porno For Pyros, Deconstruction, The Panic Channel), solo albums, and reunions of varying durations, though Avery has generally declined.

They’ve managed two further studio records, the first of which, 2003’s Strays, had enough vim and vigour about it, especially the incendiary Just Because, to suggest the old spark hadn’t totally flickered out.

But they didn’t match the towering achievements of Nothing’s Shocking and Ritual de lo Habitual.

I bow to the inevitable and leave the last word to Perry Farrell:

“If you ask me, I think it’s one of the greatest records of all time. That record is so beautiful and great to me, because it’s given me material that I can do for the rest of my life. I can do songs like Three Days, Stop! or Been Caught Stealing around the world, and I will be welcomed, and I will be celebrated, and I will get hugs and kisses.”

[paypal-donation]