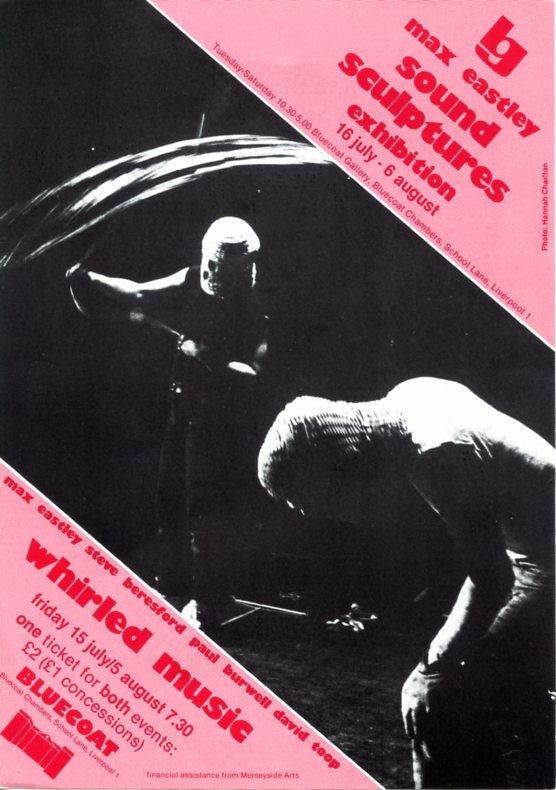

Whirled Music (Credit: Forced Exposure)

In a very personal tale Getintothis’ Jono Podmore recalls the gig that changed his life, the death of the NME and how data harvesting threatens our personal identity.

On Friday 15th July 1983 I went to the Bluecoat Chambers (as it was known at the time) with my mate Rob Callow to see a performance that I vividly remember to this day and which has had an impact on my life and work ever since.

Years before Paul Simon’s Graceland album had sparked the interest in non-Western music that became known as ‘World Music’; Max Eastley, Steve Beresford, Paul Burwell and David Toop had created, toured and recorded something much more sophisticated than the banal and at times exploitative cultural tourism of World Music. Their creation was Whirled Music.

The performance of Whirled Music I attended was in the main hall at The Bluecoat. Between the performance area and the public a net had been hung. Behind the net was a huge collection of mysterious and bizarre objects that were either long and thin themselves or were tied to pieces of sturdy string or rope. Lights were dimmed and on came the performers.

Their appearance itself was part of the show. Their faces were covered: they were wearing elaborate wicker baskets on their heads, heightening the mystery and lending the scene a ritual, even warlike aspect – referencing African and South-East Asian cultures. They were also all wearing gloves…

Bluecoat Whirled Music flyer ’83 – courtesy of Bluecoat

It soon became clear that the net, the masks and the gloves were purely practical safety concerns as the performance began. One by one the objects were picked up and swung around the players heads producing over the length of the show a fantastic and surprising variety of sounds from delicately musical to terrifying visceral noise.

David Toop: ‘Many of the instruments were made (and repaired) by Max Eastley who also suggested the idea of a piece restricted solely to whirled instruments. The notion evolved after he had seen Paul Burwell whirling heavy Chinese cymbals and banging them violently on the floor producing spectacular Doppler effects.’

In addition to variations on traditional instruments such as the bullroarer, Whirled Music also made use of whirled whistles, hand drums, radios and microphones; tubing with mouthpieces, other pipes, kid’s toys, bells and gongs.

Bullroarers “are made with a flat piece of wood or similar material, sometimes with a sawtooth profile. The size can range from the very small, producing a malevolent buzzing, to sizes around 2 or even 3 feet long, producing sounds in the infra-sonic range (and causing extreme tiredness of the arms).”

The Director of the Gallery at the time was Bryan Biggs:: ‘I was at that gig and in fact nearly ended up being one of the performers as Steve Beresford’s train was delayed and I was asked if I could stand in – no-one would know it wasn’t Beresford as I would be disguised by a protective wicker helmet, and all I’d have to do was whirl stuff around on lengths of string and elastic!

… We managed to get Granada TV to feature it (with Tony Wilson) though it only went out the evening of the gig so it didn’t help increase the audience. I wonder if the footage still exists.’

The Bluecoat at 300- an oasis of art, music and creatiivty in the heart of Liverpool

Producing sound by whirling an object produces two natural auditory phenomena – the harmonic series and the Doppler effect.

If you take a column of air in a tube and then excite it into vibration, it begins to resonate at a fixed pitch, in the same way that plucking a string under tension produces a certain pitch. This is how a flute or a whistle works, and by covering up the holes you change the length of the column of air thereby changing the pitch, again like changing the length of a string.

But the difference with a vibrating column of air in a tube is that as you increase the amount of energy used to excite it, eventually, along with getting louder, it produces another pitch. This pitch is exactly double that of the first note produced: the pitch created if the tube was exactly half its length i.e. an octave higher.

As you increase the energy yet further it goes up another leap, this time going up by a smaller amount: a perfect fifth. Next step is a fourth, then a major third. This ever-decreasing series of intervals, the harmonic series, carries on into microtones but the ratios remain fixed.

If you agitate the air in tube by whirling it a round your head – it will produce the same, harmonious, naturally occurring sequence of notes.

The Doppler effect ‘is the name given to the apparent change in frequency of a moving source, or the apparent change in frequency of a stationary source received by a moving hearer… the best example of this effect is when a train goes through a railway station.’

The above quote is from David Toop’s sleeve notes from his 1980 album release of recordings of Whirled Music on his Quartz label. One side is a live recording of a performance from Birmingham in 1979; the other “No Audience” side comprises 7 shorter recordings, a number of which are outdoors giving them a field recording quality.

The album was reissued this year in a gatefold sleeve with a wonderfully complete booklet and sleeve notes, on Oren Ambarchi’s Black Truffle records – reviewed in Getintothis’ Album Club:

‘The restrictions of the whirling process make the No Audience side in particular very natural sounding. The process itself controls extremes of volumes and peaks; producing gentle rises and falls in intensity. The Doppler effect and the harmonic series that whirling produce are fundamental natural acoustic phenomena, so the pieces sound like frogs, insects, birds or the wind in the trees.

The Audience side is much more active and noisy, even transgressive in places; that being the spirit of the time in Thatcher’s Britain. There is a bigger range of sounds: more percussion in particular, giving it more crowdpleasing dynamics.’

Whirled Music Cover – courtesy Black Truffle Records

One of the important creative principles Whirled Music demonstrates is how restriction of method fires the imagination and creates such unity in the finished pieces. Wanting to express something but with limited means pushes creativity into new areas and produces new methods itself.

This was something I discovered in depth with Metamono. Set up in 2010 we created a manifesto as a set of unbreakable rules and restraints on what we could use and how. The result was that rather than inhibiting our creativity, a genuine outpouring of work ensued: 2 albums (one a double), EPs, film soundtracks and international touring.

Contrast this with the musicians we all know who have software in their computer that fulfils every possible creative option. Writing, recording, treatment, mixing, remixing, mastering: whatever you want, wherever you want to go. But where is the new music?

The conventions of 4 on the floor dance music or landfill indie are stricter and as restricting as ever. Grime offers a little more leeway but is arguably as much a literary form as a musical one. We have been given all the options and it’s made us culturally immobile.

Things were very different in the 80’s when Rob and I first saw Whirled Music. The bemoaning of the demise of the printed NME of late has caused people to cast another eye on this period. Ex-Melody Maker journalist Taylor Parkes for example:

‘The death of the NME is the consequence to me of the death of a particular part of our culture… when you look at the real death of the NME, the spiritual death which was in the late 1980’s you understand that the NME couldn’t exist any more as it was, not within the mainstream because that moment had passed. It belonged to a post-war moment when a lot of things aligned improbably… People in Britain were rich enough to think about non-essential stuff but poor enough to be dissatisfied.

There was enough tech to enable mass communication but not enough to enable complete withdrawal from culture and suddenly almost anything was permissible because we lived under threat of the bomb and we’d just beaten Hitler, and capitalism took a while to catch up with pop culture.

So after a few twists and turns you end up with this situation where the NME could be something as illogical as a music industry journal and consumer guide whose primary purpose was to undermine the whole concept of the music industry and consumers, though not the concept of guidance.’

This special little window before capitalism caught up with pop culture allowed not only ideas like Whirled Music and the LMC that spawned it to exist, but also for it to become an event at the Bluecoat.

And not only that, an event covered on mainstream regional TV by journalist Tony Wilson, whose Factory Records label proudly declared itself not to be a business but “an experiment in humanity”. Pretentious? Most definitely – but the experiment produced the magic of Joy Division, A Certain Ratio, Durutti Column etc.

Events like Whirled Music at The Bluecoat were not only inspiring musically, especially to that pair of 18 year-olds in the audience, but also gave us the sense that our broad, transgressive, creative culture was the mainstream. This was the most inspiring thing of all. If you had the idea and the courage to pursue it, no matter how pretentious it could see you interviewed in the NME or appearing with Tony Wilson on Granada TV.

Later that summer I moved to London and on Aug 19th 1983 I saw Einstürzende Neubauten at Acklam Hall. Another astonishing show very much of this time. The hall was packed out and swelteringly hot, Molotovs were thrown in to the crowd, fountains of sparks were flying. The concrete of the building itself was being attacked by a gang of seemingly possessed Berlin punks.

I went home and formed a band.

To quote David Toop‘s sleeve notes again, the Whirled Music events were somewhere between “composition, installation, and improvisation” and that easily describes the Einstürzende Neubauten gig and demonstrates a link in the freedom of thought at the time. Freedom that extended beyond the definitions of the forms themselves.

Just another few weeks after the gig at Acklam Hall I was immersed in the Notting Hill Carnival for 3 days. An encounter with a profoundly rich but previously excluded culture, which was also knocking on the door of the mainstream, despite the institutional racism that was rallied against it.

That window between punk and the full commercial exploitation and therefore control of popular music and culture engendered a freedom of thought (and therefore rejection of racism) in those of us lucky enough to live through it.

That window of creativity has now been shut for over 30 years.

Corporate manipulation of our culture now extends to the very foundations our personal identity, even our gender and sexual orientation. As is being exposed in the enquiry into data harvesting from social networks, the corporate capitalists and extreme right view popular culture as a tool – a weapon in their armoury to control and subvert our taste, our fears and our identity in order to generate markets and prevent us from opposing their power at the ballot box.

Those of us who did breathe the air through the cultural window from 1977 to 1987 would do well to revisit Whirled Music and try to find new questions for our now utterly circumscribed culture.

We need to impose our own restrictions and find our own ways out of them, not accept the “freedoms” handed to us by the corporations. Because subsequent generations may never forgive us if we don’t at least offer them a way out of the cultural control they now suffer.

Thanks to The Bluecoat, Bryan Biggs, David Toop, Oren Ambarchi and Colin Taylor

for their assistance with this feature.

[paypal-donation]