Arthur Lee and Love

With the 50th anniversary of Da Capo album, Getintothis’ Paul Fitzgerald reflects on the tip off that led him to discover Arthur Lee’s incredible psychedelic band, and his lifelong love of all things Love.

One afternoon in 1985, I was sitting upstairs in the Royal Court talking to Kenny. Kenny was, and is, a mate of mine. He played guitar in a band called Kit, and I was a hanger-on of various Liverpool bands, and attempting to form my own, something I later went on to do, several times, with little or no discernible success.

But Kenny was in Kit, they did John Peel Sessions, had cool semi acoustic guitars, flattops, and everything. They got their hair cut in Vic’s on Whitechapel. They were proper, they rehearsed in The Ministry, their singer Lin was a good mate of my hero, Mick Head. In fact, Kit were mates with everyone who was anyone. You’d see them hanging out in the Armadillo Tea Rooms, or the old Everyman Bistro, or, even cooler (then), The Albert on Lark Lane. I was 18, and ridiculously impressed by all this. I’m 49 now, and truth be told, I’m still just as impressed by all that.

We were in the Royal Court that afternoon for an event celebrating Radio City’s tenth anniversary of broadcasting in Liverpool. It was called Ten Bands, Ten Years, Ten Bob. I probably don’t need to explain what the event was about. I don’t remember all the bands who played, but Personal Column, Western Promise, A Broken Promise and South Parade were all part of the day. Someone has suggested The Builders, who I liked, also played, but I really don’t remember whether that’s true or not. I didn’t really like many of these, to be honest, but it was a day in the cold and dark environs of the Royal Court, the bar was open, I was 18, and it only cost 50p. Best of all though, The Pale Fountains, my Gods, were headlining. So it was worth a 10 hour wait in anyone’s money.

Kenny and I were talking about the bands on the bill, their few plusses, and their many minuses. Balancing the pros and cons objectively and in depth. You know, as you do…..they’re shite….these are alright….nah, they’re shite too..and on and on. That kind of thing.

The conversation inevitably turned to the headline act, The Pale Fountains. Just a couple of months after the release of their second and final album From Across The Kitchen Table, they were at the absolute top of their game. Mick Head’s writing had taken on a slightly harder edge from their first LP, there was less woodwind and strings, but still plenty of brass and more distorted guitar, while still retaining their folk-pop credentials, I was drawn to this band initially a couple of years earlier, by their stubborn insistence on standing outside of expectations, away from what everyone else was doing.

In many ways, that may have been their downfall, but to me, it was a pretty cool act of defiance for them to release their first album Pacific Street at that time. When the record and music shops were filled with people searching out the new synths and drum machines, the new analogue beats and beeps, Mick Head wrote an album of sensitive soulful songs, with flutes, cellos, steel drum and brass accompaniments. I loved that attitude, that outsider-ness. Plus, like Kit, they had boss haircuts and cool guitars. That helped, like.

Lost Liverpool looks at the Liverpool 1990 festival, where Shack and Arthur Lee combined forces

I remember Kenny’s words. The actual words. Like it was yesterday.

“Well if you like the Paleys, you should listen to Love”

Love? What did he mean listen to Love? What, or who, were Love?

I didn’t know it at the time, but what I know now, is that in that one ten word sentence, my world was about to change forever. This was to be one of those magical moments as a music lover when someone turns you onto something you’d never heard before, something which becomes such an important and integral part of your life. Something to learn from, to mark important moments, something that blows your mind every time you hear it. Something that no matter how many years go by, continues to give, continues to enrich you with each and every listen.

Kenny opened a door that day, I happily walked through it, it led me to untold places, and I’m never going back. Obviously, other people would lead me on similar journeys, down similar paths, and to similar destinations, they still do, and to them I’m grateful always, but this moment, this journey was one I embarked on almost with the belief that it was only for me, that I was the only one walking this path.

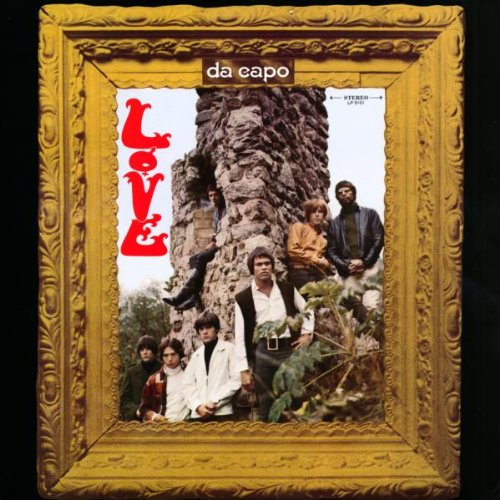

Two days later, I bunked off college early and went into town. I think I went to Our Price in Central Station. I’m absolutely certain of the price though, because I kept the sticker on it for a few months. It cost £3.49. I could get twenty ciggies for that in those days, so this was some serious investment on my part. Although it wasn’t really my money, I’d robbed it from my brother. All the way home on the 79 bus, I stared at this peculiar cover, clutched it to me close like a trophy. Seven hip looking 60s cats assembled around what looked like the crumbling chimney stack of a long since obliterated Hollywood mansion. It really told me nothing of what to expect, other than the fact that this band were from the 60s, nothing stood out.

Other than the obvious Beatles and Motown stuff we grew up surrounded by, and the work of my other obsession Ray Charles, I wasn’t really aware of many 60s artists, their scenes, and the rich and varied contribution of the many different cities. I was only just getting into The Doors, mainly thanks to the Bunnymen’s obsession with them, and my obsession with the Bunnymen. So this cover interested me. They looked cool. I liked the cut of their rag tag 1960s collective jib. This was something I could get into, I thought. Or, to use the correct parlance, I could maybe dig this?

Through the door and straight to the bedroom with my fresh and unknown treasure under my arm, and within a few minutes, my world felt, and looked very different.

From the opening of Stephanie Knows Who, all twinkling cyclical harpsichord and frenetic changes, with Arthur Lee barking his vocals manically over the top, it was an absolute game changer for me. The changes, the leaps in the dynamics, the sax solo halfway through, the dissonant guitars at the end. I’d never heard anything like it before, and I wanted more.

I remember listening to that song three or four times before the rest of the album, louder and louder each time, just trying to understand what it was. It was like an explosion of colour, a noise I couldn’t identify, and it felt like the sound of my mind being opened and painted in primary colours. And it was all over in three and a half minutes. I loved the madness of it all, the urgency, and the sound of the rule book being thrown out of the window. I expected the next track to feature even more bent minds and twisted ideas.

What I got with Orange Skies, was one of the most beautiful love songs I’d ever heard then, or for that matter, since. Here was the writing of Bryan Maclean at his absolute sweetest, purest and most vital. The flute dancing through and around the loose jazz rhythm section and Arthur’s soft, warm vocal all an absolute joy to behold. It makes me smile every time I hear it, it was the second song I played when my eldest daughter was born on a beautiful summers morning years later (the first being the one she was named after), and it will be the song they carry me in to the crematorium to when I depart this place. Such beauty in song such never be underestimated.

Que Vida, all heady sun kissed Spanish vibes, heavy on the flute and led with a swirling Hammond organ, and its nursery rhyme lyrics sounding like a spell being cast, had me enthralled. It all felt like I was leaving to go somewhere, on a journey to an as yet unknown destination. I liked the view, too.

Seven And Seven Is exploded into view, energetic and essential. It’s all yelled vocal, crashing chords, distorted bass sounds and a near impossible to record “Snoopy” Pfisterer drum track. The song was recorded a few months before the rest of the album, and Pfisterer was subsequently moved to keyboards in favour of Michael Stuart taking his place behind the kit.

The tales of the recording of this one song, one of Arthur Lee’s best ever compositions, are as legendary as the song itself, crazed drug fuelled chaos was the order of the day. Although still only recording their second album, cracks were beginning to form with this line up, unbridgeable gaps and immovable obstacles in the landscape were appearing, bad feelings and mistrust ruled the hour. That pent up angst shines through in Seven and Seven Is right up to the moment the bomb goes off near the end. The sheer energy and fury in this song still astounds, it really is something else, a whole other level of rock and roll greatness.

The intricate, fluid Baroque fingerpicking style on The Castle, with Arthur’s poetic lyric and the Bach inspired harpsichord arrangement makes for a grandiose and celebratory almost English country garden vibe. Its simple, pretty and delicate. The timing changes, the lifts from classical to flamenco all adding depth and breadth. Always an interesting listen that consistently offers up something new with each listen.

The Castle is the name of the sprawling Hollywood mansion the band shared for a couple of years, as the money and drugs rolled through the gates, and their unity and togetherness fled out the back. The mind boggles as to what went on within its many walls. In the film Love Story, Arthur revisits the place in something of an altered state, and attempts to remember those days, not with any great level of success it must be said.

Side one of Da Capo ends with the beautifully enchanting She Comes In Colors, which is rightly and widely considered to be Lee’s greatest work. It’s a strange and dreamy poetical piece, which Johnny Echols remembers as being difficult to record because of the chord changes.

Even for Johnny Echols, one of the most accomplished and brilliant underrated guitarists ion his generation, this was a challenge. Again, flute and harpsichord unite to give the song an otherworldly atmosphere, and to lift it through the dynamic changes that Echols talks about. On that first listen, it was an addictive, entrancing and spellbinding sound, which, while sounding so difficult, actually came across as quite simple.

One side of one album, and quite some start on my journey of Love. Surely side two would offer more thrills, more uniquely poised and positioned sounds, more poetry?

Side two of Da Capo is one song. At just under 19 minutes, its a long song too. Revelation begins with a frantic harpsichord intro, before dropping into a chugging blues groove. It lacks any real structure or direction, and though there is the odd moment of glory here and there, its otherwise a disorganised self indulgent jam session. Stemming from a live piece intended to give each player, by this point, seven of them in total, an opportunity to shine, it probably did make sense in the live setting.

On record though, it makes little or no sense. It didn’t thrill me when I first heard it, and still doesn’t. The difference between that side of this album and so much of the rest Love’s work is astounding. Miles apart. I’ve lost count of the amount of times I’ve listened to side one of Da Capo. Thousands, I reckon. But I could count the number of listens I’ve given Revelation a spin on just one hand of a four fingered man. It does nothing for me, and at the time, I found that a little disappointing.

But I was undeterred. I needed to know more. I wanted more Love in my life. I wanted to hear more, to know more. Kenny was right all along. Within a few weeks, I’d bought the eponymously titled first album, and I was on my way. The incredible Forever Changes came as a gift that Christmas, from the brother I robbed earlier, and is still blowing me away.

Those first three Love albums show a real sense of progression and development, as the unique sound of the band is forged and shaped. The story of the band is one of chaos, addiction, power struggles, and mistrust. Just like the stories of many great bands.

Click here for new albums, classic albums and albums of the year

By the time of Forever Changes, they were falling apart and that original line up would go their separate ways soon after. That particular magic was over. But as a statement of intent, as a work of art, and a sheer declaration of artistic and creative genius, I would put those three albums up together against any other work at that time. They stand up well in comparison with The Beatles and Beach Boys recordings of the time, and that to me is merely an indicator of just how underrated Love were then and are now. I hate the expression ‘cult band’, its a meaningless and futile title, and in the wrong hands, its little more than an insult. But here we have a band that are undoubtedly adored by far too few people.

Here was a band, a multicultural band no less, featuring two men who had seen the racism and segregation of the deep south, who knew it well, uniting together with a central common love of music, who’s only mission was to play together, to write great songs, play great shows and share their love of music with a wider and hopefully accepting world.

So Kenny was right at that Pale Fountains gig.

Seven years after that conversation, I got to see Arthur Lee live, with Shack as his band. It was an incredible night, and an incredible feeling. I got to meet Arthur. I thought of Kenny that night. This year, I got to see Mick play with Johnny Echols and Love Revisited. And to top it all, I took Johnny for a coffee and some cake. We had the most incredible conversation about his life in the band and since. It was a really special couple of hours, that I’d dreamed of for so long. I thought about Kenny that day too.

A few days later, Johnny Echols appeared with a host of Liverpool talent as part of From Liverpool With Love commission at LIMF in Sefton Park. I stood in that field, with a fixed grin as I watched. I gazed across the crowd, and there, stood grinning with a beer in his hand, was Kenny. 31 years after our original conversation, I was able to go and thank him.

Of course, in reality, to most people, none of this matters. It is entirely inconsequential. It changes nothing in their lives, it adds little. It neither asks questions, nor provides any answers. It’s merely a personal reflection. But if someone picks up a copy of Da Capo and gives it some fresh ears because of it, well…

Kenny gave me Love, Our Price gave me Da Capo, and my world was never the same again.

[paypa-donation]